Country: Portugal

Title: Tabu (2012)

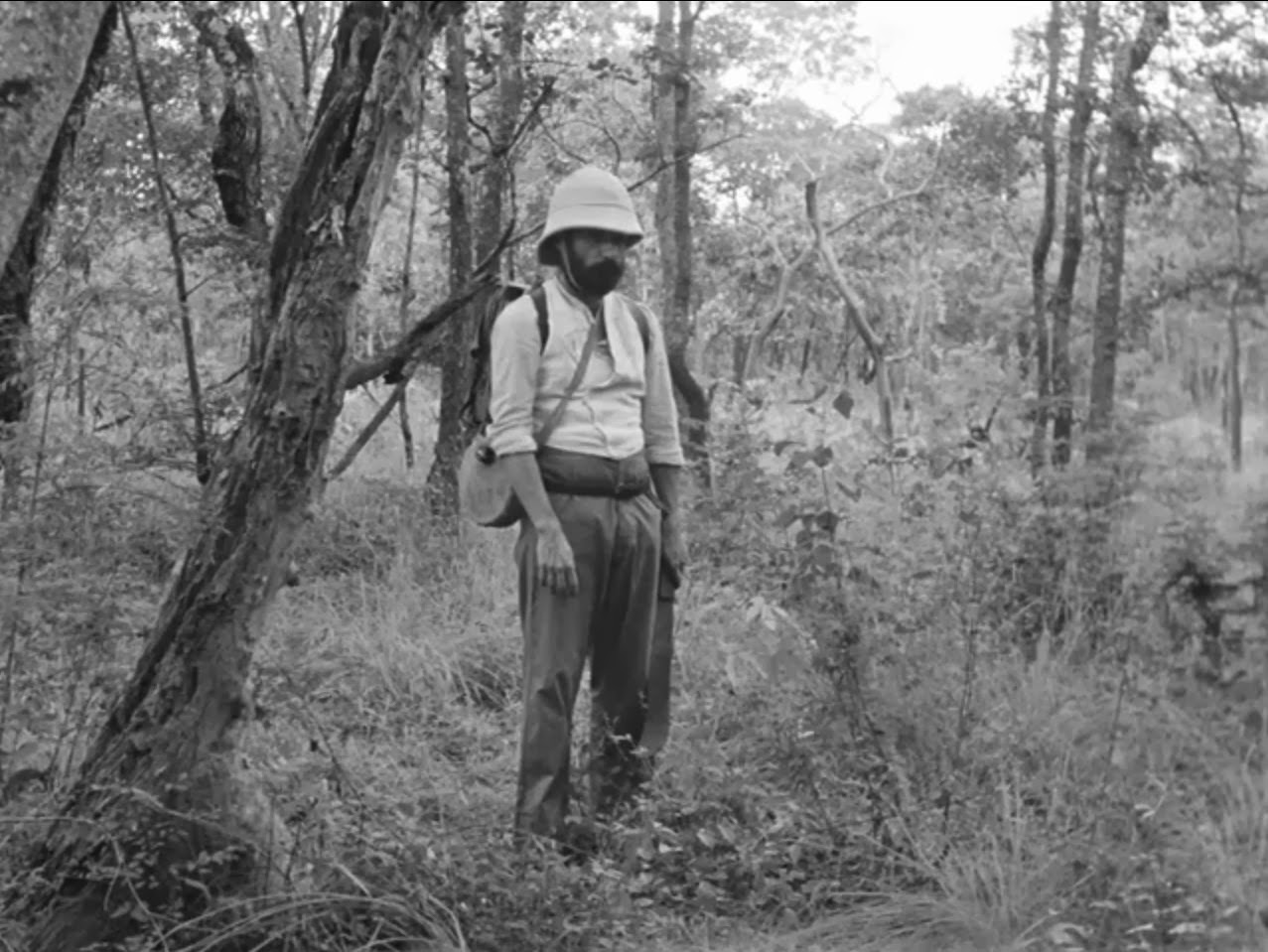

Tabu opens on a pith-helmeted

Portuguese explorer in Africa whose melancholic slump caps off his rather

absurdly pathetic appearance. A narrator explains that fatalistic romantic tragedy has

spurred his expedition into the Serengeti. Observed by his native caravan, he

drops into a river and is consumed by a crocodile, which is seen accompanied by

a ghostly beauty in later years. This turns out to be a short film watched by

Pilar, a middle-aged activist in contemporary Portugal trying to get in touch

with her estranged daughter. Though she has her hobbies, her causes and an unrequited suitor-of-sort in the form of a smitten painter, Pilar’s attention

becomes focused on her neighbor, an elderly woman named Aurora.

Aurora comes

off as vain and ridiculous: she throws away the allowance granted by her

daughter (also estranged) at a casino on the basis of a strange dream,

mistreats her stoically exasperated but grimly loyal African maid Santa and

suffers from increasingly erratic and guilt-ridden paranoid delusions. Aurora

suddenly dies, but communicates a message to Santa and Pilar to contact a

mysterious man named Gian-Luca Ventura. This latter turns out to be a former

flame, who attends Aurora’s funeral before narrating the second half of the

film. He sits down with Pilar and begins by saying, "She had a farm in Africa." Here the story, not to mention the tone, shifts a second time, taking us

back to the waning months of colonial rule before Mozambique’s revolution. A

young and fiery Aurora, renowned big-game hunter and wife of a successful

tea-farmer, lives with her pet crocodile on the slopes of Mount Tabu. Her

exhilarating life climaxes in a risky affair with a young Ventura, then a dashing playboy, but ends in violence and heartbreak.

Portuguese cinema has long labored

under The School of Reis, a movement that advocated a rather academic

docufiction aesthetic that once reinvigorated the industry. It helped

established the international profile of Portugal’s best-known auteurs like

Manoel de Oliveira (104 and still making films!), Joao Cesar Monteiro (consummate

satyr and provocateur) and Pedro Costa (sincere but terminally sluggish

spelunker into urban poverty), but it quickly led to a stagnant cycle of

stilted slow cinema productions that continue to wow niche critics, while

leaving me and most viewers rather bored. And then out of nowhere comes Miguel

Gomes, a former Reis acolyte lurking in obscurity who, while not rejecting

formal rigor and stylized artifices, has managed to breathe new life into

Portugal’s art cinema and imbue it with adventure, passion, sorrow, whimsy and

structural daring.

The heart of Tabu’s story is

undoubtedly the second half (titled Paradise) but the less-loved hour-long

first half (Paradise Lost) is both a devious meditation/misdirection on

the changing role of cinematic protagonists and a critical component of Gomes’s

exploration of the tragedy of time; the transformation of Aurora from the

heart-stealing heroine of her youth into a harmlessly gauche wreck regarded

with well-meaning pity by friends, family and her last lingering servant. And it’s imperative that

we see the latter image of Aurora first, and fall into the trap of writing off

the silly old lady, before realizing the vastness of experience and emotion

that her life, and by extension all lives, contains.

Shifting attitudes are also a central

theme of Tabu on other levels, too, including race relations and the politics

of filmic representation. Colonialism is today almost solely situated somewhere

between an atrocity and an embarrassment in European films, so it makes Tabu

something of an old-fashion throwback to whole-heartedly romanticize Aurora’s

past. This is not naivety on Gomes’s part: the film’s title, a reference to a

1931 ethnographic documentary by Murnau, is just the first clue that Gomes

knows using Africa as a backdrop for exotic adventures and European romance

is problematic. It’s also not mere cynicism or satire, as the emotional sweep

of ‘Paradise’ is rendered with exquisite detail and seductive earnestness. The

actual tone is hard to put a finger on (always a good thing!), managing to draw

you into, by turns, melancholy, mystery, romance and adventure while elements

of danger, criticism and socio-political condemnation peep through, contrasted with and

heightened by our retroactive perspective.

Gomes shoots in meticulous almost

gothic black-and-white and his images alone make this film incredibly

watchable. The second half of the film, probably intentionally, makes the first

half (which is still quite well-composed) feel cramped and mundane by comparison.

Paradise is curiously told with only sound and Ventura’s hypnotic narration,

but no dialog, despite mouths moving. It's as though you were watching old home

videos, but with world-class cinematography. This ties in to the way Aurura loses

her voice both metaphorically and finally literally with age. There are other strange

parallels throughout the film, too, like the crocodile prologue, Aurora’s dream

monologue, a shopping mall jungle that foreshadows Ventura’s flashback and the

beguiling narrative dead-end of Pilar and her neighbor’s absent daughters,

perhaps implying that some secrets yet remain even after all has seemingly been

revealed.

.jpg) |

| A zoo and a nursing home waiting room from the first half of Tabu, that visually foreshadow the African settings of the second half. |

My Favorites:

Tabu (2012)

Belarmino

The Green Years (1963)

Aniki-Bobo

Major Directors:

Pedro Costa, Fernando Lopes, João César Monteiro, Manoel de Oliveira

Pedro Costa, Fernando Lopes, João César Monteiro, Manoel de Oliveira

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment